I had the privilege of helping the Washington Post on two stories (read them here and here) last week about Esteban Santiago, the Anchorage man who shot five people at the Ft. Lauderdale airport.

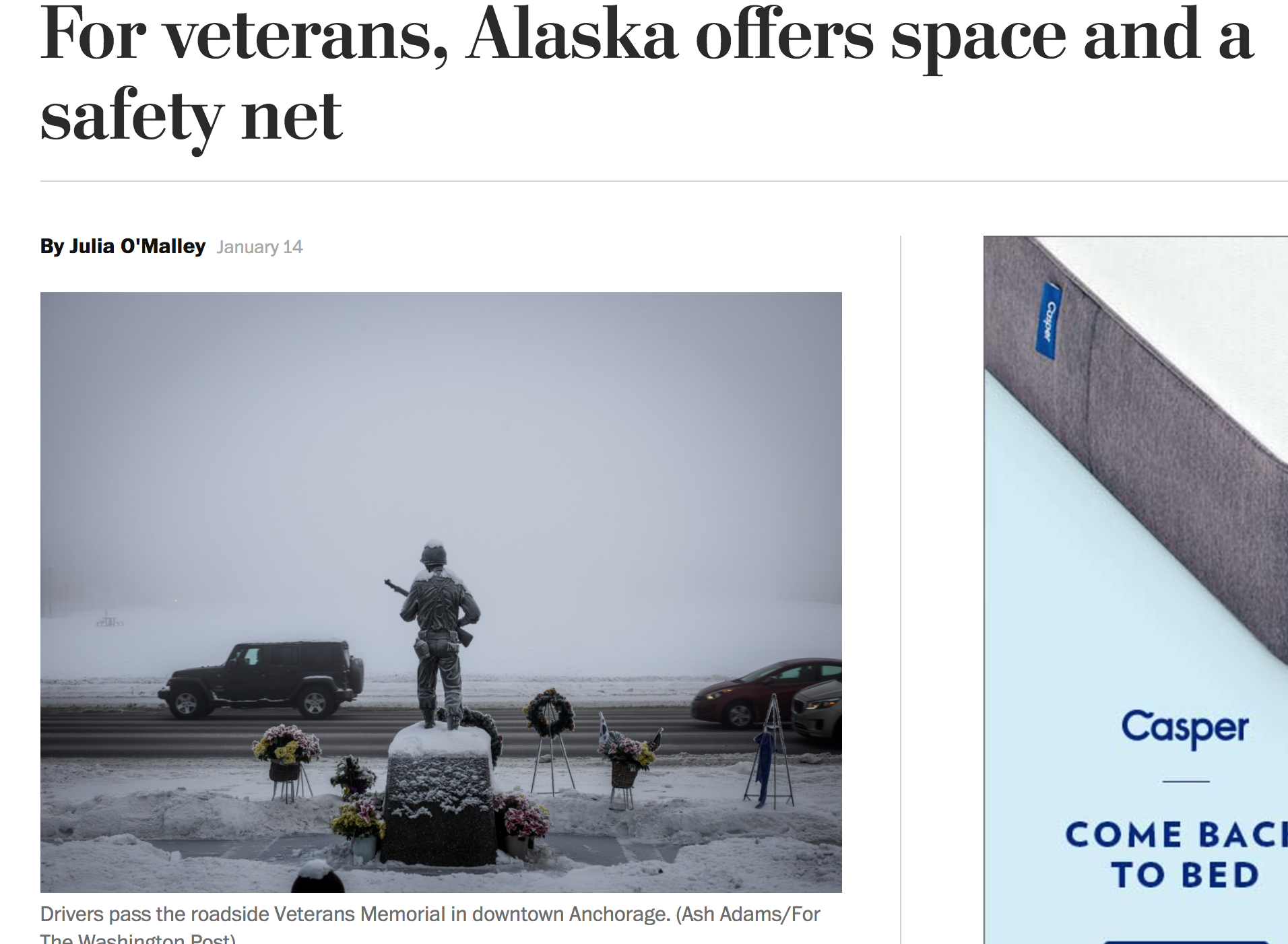

Then, over the weekend, I had a story of my own published in the Post that helped to provide context about Alaska law, mental health care and veteran’s culture here. To report that story, photographer Ash Adams and I spent several days talking to vets and visiting a VFW and an American Legion Hall, which was truly a pleasure.

The Washington Post story begins:

ANCHORAGE — Monday night was lasagna night inside the strip-mall storefront of VFW Post 9981. Clemson was still behind Alabama on the big screens as regulars trickled in. At the bar, Joe Federmann considered how Esteban Santiago fell through the social safety net Alaska has for veterans.

A young combat vet, Santiago lived for several years in this town of 300,000 before he boarded the plane that took him to Fort Lauderdale, Fla., where the FBI says he shot five strangers at the baggage claim. Santiago showed signs of serious mental illness and a propensity for violence the year before the trip, investigators say. Federmann wondered whether he had signed up to get mental health care from the Department of Veterans Affairs. There is good help available for vets, he said, but they have to take it.

“The thing about it is, a lot of veterans don’t feel they want to seek that help because they think they don’t need it,” Federmann said.

It has been more than 40 years since Federmann, 71, saw a man killed by a rocket in Vietnam, but the memory is still searing, he said. When he came back from the war, he and his family moved to Alaska. He found peace in the vast wild landscapes, the fishing and a community of veterans who understood him, he said. He also had good care at VA. When he dies, he would like his ashes spread over an Alaska mountain range, he said.

There are more vets per capita in Alaska than any other state. One out of every three people is either military or a dependent, according to Verdie Bowen, director of veterans affairs for the state. Alaska offers vets opportunities in oil fields, health care, mining, aviation, military contract work and the federal workforce. In a place where bears eat out of trash cans and moose rut in cul-de-sacs, nobody makes a big deal about owning guns. And Alaskans tend to value self-reliance and practicality, Bowen said.

“A lot of the veterans come up here; they want to be on their own,” he said. “A lot of veterans are of an independent mind-set.”

Read the rest here.